Firefly Aerospace and Aerojet Rocketdyne have announced a strategic partnership to collaborate on rocket propulsion, an agreement that could lead to Firefly’s use of Aerojet’s AR1 engine in a new medium-lift launcher.

The companies announced the cooperate agreement Oct. 18, and revealed new details about the partnership Oct. 22 in a press conference at the International Astronautical Congress in Washington.

Firefly is proceeding with development of the Alpha small satellite launch vehicle using the company’s own engine designs. The Alpha rocket’s first launch is scheduled no earlier than February 2020 from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

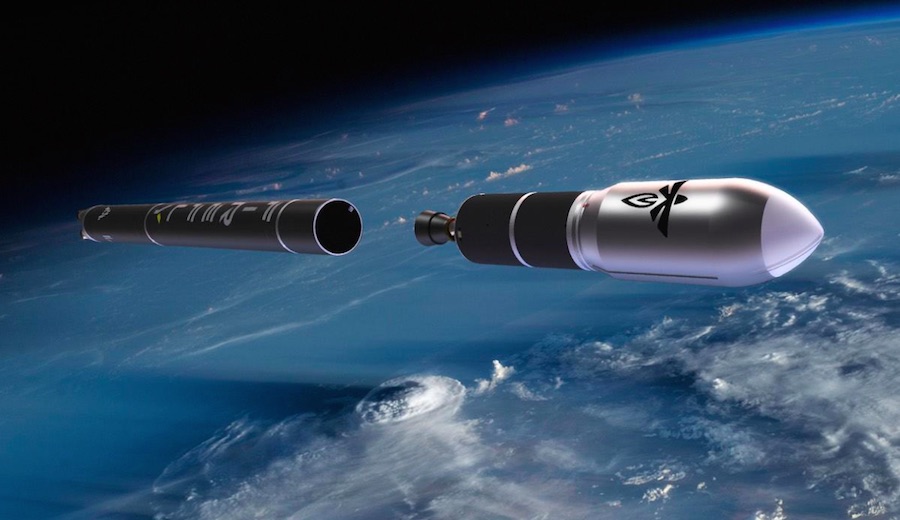

While Firefly engineers prepare for the final phase of ground testing before the Alpha’s first launch, the company is already eyeing a larger rocket named Beta.

Tom Markusic, Firefly’s chief executive, said the company has moved on from its original plan to create the Beta rocket from three Alpha first stage boosters, forming a triple-body rocket like the Falcon Heavy or the Delta 4-Heavy. Firefly instead plans to design the Beta rocket as a single-core rocket.

“For that launcher, obviously, there is going to be a need for a domestic high-performance booster for that stage,” Markusic said Oct. 22. “Firefly presently does not have in its corral of engines a large booster engine that we can put on Beta. We see AR1 as offered by Aerojet Rocketdyne as a really strong contender to provide an economic and reliable propulsion for Beta.”

The two-stage Alpha launcher will be capable of hauling up to 1,388 pounds (630 kilograms) of payload to a 310-mile-high (500-kilometer) sun-synchronous polar orbit. Four Reaver engines will cumulatively generate more than 160,000 pounds of thrust on the Alpha’s first stage, and a single Lightning engine will power the Alpha’s second stage.

The Reaver and Lightning engines, like Aerojet Rocketdyne’s AR1, consume kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants.

The new Beta rocket architecture, assuming it uses an AR1 first stage engine, could deliver more than 17,000 pounds, or about 8 metric tons, to low Earth orbit, roughly double the lift capability of the previous Beta design, according to Markusic. He said the AR1 is “ideally sized” for the Beta rocket.

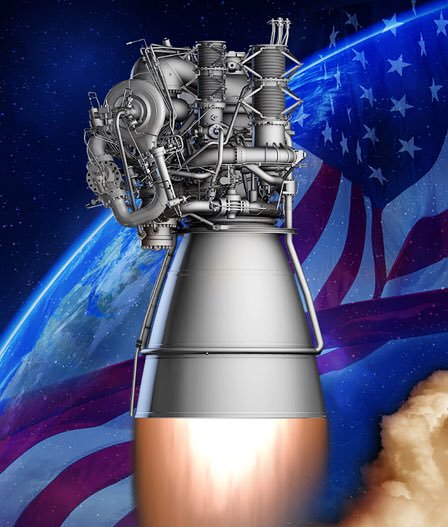

Aerojet Rocketdyne developed the AR1 engine to power the first stage of United Launch Alliance’s next-generation Vulcan rocket. But ULA last year selected Blue Origin’s BE-4 engine for the Vulcan first stage, leaving the AR1 without a customer.

The AR1 engine, which has not yet flown, is designed to produce up to 500,000 pounds of thrust at sea level, using an oxygen-rich staged combustion engine architecture.

Jim Maser, executive vice president of Aerojet Rocketdyne’s space business unit, said the company is manufacturing components of the first “test-ready” AR1 engine. The AR1’s development up to now has been funded through a cost-sharing public-private partnership between the U.S. Air Force and Aerojet Rocketdyne, which shepherded the engine through component testing and a critical design review in 2017.

“We’re manufacturing the hugest components right now, which would could call the powerhead, which is the turbomachinery and the nozzle. That’s all coming together right now, and then those parts all get sent to the Stennis Space Center (in Mississippi), which is our large engine assembly and test facility, and we’ll start putting the engine together. We anticipate having that test-ready engine put together in the first half of next year.”

The Beta rocket is targeted at a segment of the launch market once served by ULA’s Delta 2 rocket, which retired last year, Markusic said.

Firefly, based in Cedar Park, Texas, says it expects to sell a dedicated Alpha launch for $15 million per flight. The company has not disclosed a price for the Beta.

“That vacancy of Delta 2 has left an opportunity for a modern launcher to come in that can have perhaps a better price point than Delta 2,” he said.

Markusic added that the Beta rocket could debut two or three years after the first successful launch of Firefly’s Alpha rocket.

Firefly is not just aiming for the Delta 2’s market. The company is outfitting the Delta 2’s former launch pad at Vandenberg for the first flight of the Alpha rocket early next year.

Firefly has finished qualification testing of the Alpha ‘s second stage at the company’s test site in Central Texas.

“We’ve qualified the second stage of the vehicle, which in many ways is the hardest part because all of the electronics, all the brains of the rocket, are in the second stage,” Markusic said. “We completed a fully integrated second stage qualification test of all the avionics, structure and engines.

“The last big piece we need to retire from a risk perspective is the Stage 1 engines, (which) we call Reaver,” he said.

In recent weeks, Firefly has commenced testing of four Reaver engines at once on a test stand in Briggs, Texas. Next month, engineers will attach four engines to an Alpha first stage structure to run a full-scale test.

Then Firefly plans to ship the Alpha first and second stage qualification units to Vandenberg to rehearse launch site handling and processing procedures, culminating in a static fire on the launch pad, Markusic said.

Firefly is modifying the Delta 2-era rocket processing hangar at the Space Launch Complex 2-West launch pad at Vandenberg. The Alpha rocket will not require the launch pad’s mobile gantry or fixed umbilical tower, which will be demolished, according to Markusic.

The Delta 2’s launch mount at SLC-2W has also been removed in preparation for Firefly’s Alpha rocket, which will be assembled in a nearby hangar, rolled out, and lifted vertical on a transporter/erector structure.

Aerojet Rocketdyne’s collaboration with Firefly will not be limited to the possible use of the AR1 engine on the Beta rocket. The engine contractor will provide 3D-printing expertise for key Reaver engine components, the companies said in a joint statement.

“Alpha’s pretty far along,” Maser said. “We want to do anything we can in the short run to help them make the Alpha successful, to launch on a regular basis, and to build up that business base, and then expand Alpha. We want to improve its performance.”

Aerojet Rocketdyne will have a greater role in Alpha’s block two upgrade on the first and second stage engines. The upgrade will raise the Alpha’s performance to sun-synchronous orbit to greater than 1,763 pounds (800 kilograms), according to Firefly.

“These contributions will include expanded implementation of additively manufactured elements to reduce cost and increase reliability, as well as technical input to increase engine performance,” the companies said in a joint statement.

Firefly is one of nine companies selected by NASA last year to compete for contracts to ferry scientific payloads to the moon through the space agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services, or CLPS, program. Firefly has partnered with Israel Aerospace Industries to build a U.S. version of the robotic Israeli Beresheet lander, which crashed on an attempt to become the first privately-funded spacecraft to land on the moon in April.

Another project in Firefly’s portfolio is an electric space tug named the Orbital Transfer Vehicle, which could carry payloads to multiple orbit on the same mission, or deliver satellites to altitudes and inclinations outside the reach of the Alpha rocket by itself.

During the Oct. 22 press briefing in Washington, Markusic identified electric propulsion as another area ripe for collaboration between Firefly and Aerojet Rocketdyne, enabling missions to the moon using small launchers.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.