Update 10:10 p.m. EDT: SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy second stage completed its third burn and deployment of the GOES-U satellite.

The finale in a series of critical weather satellites for the United States surmounted some weather challenges as it began its journey to join its three fellow satellites on orbit. The Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites-U (GOES-U) satellite is designed to provide critical weather, climate and solar data to meteorologists and other parties to enhance the safety of people and property.

The spacecraft, managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), was launched to a geosynchronous transfer orbit onboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket. Launch of this fourth and final satellite for the GOES-R series happened at 5:26 p.m. EDT (2126 UTC). As of 6:12 p.m. EDT (2212 UTC), the upper stage of the rocket was in a coast phase with the GOES-U satellite attached to the payload adaptor.

During a prelaunch press conference, Brian Cizek, a launch weather officer with the 45th Weather Squadron, noted that there was only a 30 percent chance of favorable weather during the two-hour launch window. That improved to about 50 percent in the early part of the countdown and then 70 percent in time for launch.

The main weather concerns heading into the launch were the cumulus cloud rule, the anvil cloud rule and the surface electric fields rule.

“We evaluate a set of ten lighting launch commit criteria that are designed to protect not just against natural lightning, but rocket-triggered lightning,” Cizek said. “The rocket can actually trigger its own lightning strike if it flies through or near a cloud that could hold a charge by increasing the electric field in the atmosphere by up to 100 times. So, that’s what these rules are designed to protect against.”

A pair of sonic booms shook Florida’s Space Coast as SpaceX recovered the two side boosters on the three-core Falcon Heavy rocket, tail numbers B1072 and B1086. They touched down at Landing Zone 1 (LZ-1) and Landing Zone 2 (LZ-2) at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station a little more than eight minutes after liftoff. The core booster, B1087, was expended following separation with the rocket’s upper stage.

All three of boosters being used on this mission were brand new.

“With reusability, we’re reusing our vehicles, but we also need to replenish the fleet. And the decision that we made in coordination with the NASA Launch Services Program (LSP)was that it makes sense for us to replenish the fleet now with these new boosters,” said Julianna Scheiman, SpaceX’s director of NASA Science Missions, during a prelaunch press conference on Monday.

This tenth flight of a Falcon Heavy rocket was also the first time that a GOES-R series satellite launches on this vehicle. Denton Gibson, the NASA LSP launch director, told Spaceflight Now in an interview ahead of launch that he and his office worked with NOAA to help them adjust to a launch aboard a SpaceX rocket.

“It’s just a matter of our team helping them get familiar with this particular vehicle, how they operate, the culture, the things they need to be aware of that they may not have had to worry about on a previous mission and so on,” Gibson said. “So, it’s just a matter of our team getting them up to speed on this particular launch vehicle, which to this point has gone smoothly so far.”

Pam Calderwood, the deputy program manager of GOES-U for Lockheed Martin (the prime contractor) said during the design and construction of this satellite, they had to make some modifications to support a horizontal integration with the launch vehicle as opposed to the vertical integration used on previous Atlas 5 launches with United Launch Alliance (ULA).

“The tipping of the spacecraft, all of the mechanical, specialized equipment to do that, a lot of it had to be updated, redesigned,” Calderwood said. “And then, we had to also take a look at all of the support structure to make sure that when you have some thing that’s basically in the 11,000-pound range that you’re trying to sit on its side, to make sure that there’s the proper supports needed.”

Following spacecraft separation about 4.5 hours after liftoff, the next big milestone for the spacecraft will be the deployment of four out of five of its solar array panels, which will allow it to start charging its batteries.

“The reason that’s so important is this spacecraft needs power to survive, if there’s any issues. And so, it’s very important to make sure that we have a really good solar array deployment,” Calderwood said.

About two days after launch, they will begin the liquid apogee engine burns to raise the apogee to a geosynchronous Earth orbit. That will be done with five separate burns over a 14-day period with the last burn coming at about July 8.

Over the next several months, the spacecraft will go through operational checkouts and calibrations, before it finally arrives at its final orbital position and will be renamed GOES-19. It will function as the primary “GOES East” satellite and will work alongside GOES-18, which is the primary satellite for “GOES West.”

We’ve been getting #ReadytoGOES all month-long!

Take a peek at what our Road to Launch has looked like since #GOESU landed in Florida, and stay tuned for launch coverage today!https://t.co/xaeDRxTWgm pic.twitter.com/QuOVBXDXJy

— NOAA Satellites (@NOAASatellites) June 25, 2024

Improving the forecast

Built by prime contractor Lockheed Martin, the GOES-U satellite is designed to further enhance the ability to track and predict weather conditions, both on the Earth as well as in space. Unlike the previous three spacecraft in the GOES-R series, GOES-U includes an instrument called the Compact Coronograph-1 (CCOR-1), which was developed by the Naval Research Laboratory.

Calderwood said it was a somewhat last-minute addition from NASA, but it will provide NOAA the ability to study the Sun’s corona with much greater frequency. It’s something that, on Earth, is only truly observable during a total solar eclipse.

“The Sun, when it goes through and it has these types of geomagnetic storms or these eruptions, it can go through and create communication blackouts. It can create disruptions to power grids. I know there’s also errors in the GPS systems that can happen,” Calderwood said. “And really, what’s important is to also make sure that we’re keeping our astronauts safe. So, we’re really cognizant of the exposure, the added exposure to radiation.

“And we’re all really excited to have this new piece of equipment on there that’s going to go through and help with that early warning detection.”

.@NOAA‘s new #GOESU satellite will not just help us study weather on Earth, but also potentially harmful #SpaceWeather with the help of a BRAND NEW instrument—the compact coronagraph-1 (#CCOR1)!

More: https://t.co/uDP44QfpWg

Get #ReadyToGOES tomorrow!#CountdownToLaunch pic.twitter.com/PHKqs3iZim

— NOAA Satellites (@NOAASatellites) June 24, 2024

The goal of CCOR-1 is to provide advanced warnings of between one and four days to allow preparations to take place to account for heightened solar activity. That work will be bolstered by GOES-U’s Solar Ultraviolet Imager (SUVI) and the Extreme Ultraviolet and X-ray Irradiance Sensors (EXIS), which “provide imaging of the sun and detection of solar flares,” according to NOAA’s National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS).

In addition, GOES-U includes two primary, Earth-facing instruments, the Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM), built by Lockheed Martin; and the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI), which was built by L3Harris.

The ABI scans the Earth every 10 minutes across 16 color bands, which range from the visible to the infrared spectrum. Chris Reith, L3Harris’ program manger for the ABI, said one of the most serendipitous parts of having the recent iterations of ABI has been its ability to detect fires.

“It can pick up a fire as small as a small barn fire from 22,000 miles above Earth,” Reith said. “So, that’s really one of the most amazing things, especially with all the wildfires we’ve seen in the western United States. It’s getting a lot of use in that way.”

The Geostationary Lightning Mapper (#GLM) onboard @NOAA‘s #GOESU 🛰️ will collect data on #lightning activity to help recognize intensifying thunderstorms and tropical cyclones.

Get #ReadyToGOES tomorrow!#CountdownToLaunch pic.twitter.com/GwgYuvOH9g

— NOAA Satellites (@NOAASatellites) June 24, 2024

Looking to the future

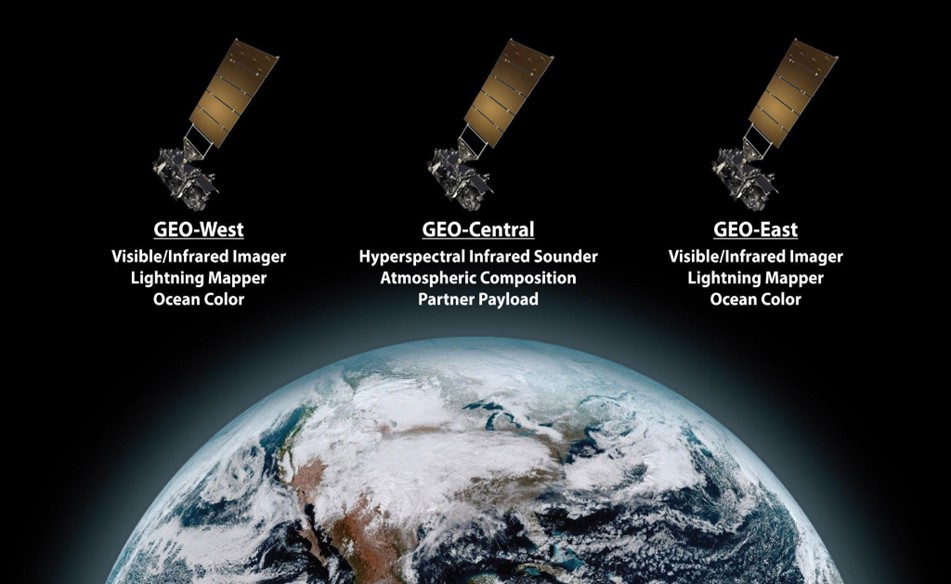

All of the learning from the GOES-R series of satellites will roll over into the next generation of weather satellites: NOAA’s Geostationary Extended Observations (GeoXO). In mid-June, Lockheed Martin was awarded a $2.27 billion cost-plus-award-fee contract to design and build the trio of spacecraft, which need to have a minimum 10-year on-orbit operational life plus five year in on-orbit storage.

BAE Systems was also tapped in late May to develop and build the GeoXO Ocean Color instrument (OCX), which “will monitor U.S. coastal waters, the exclusive economic zone, and the Great Lakes,” according to NASA.

Reith said they are also working on improvements to the ABI for the GeoXO constellation.

“The majority of the subsystems that we use on the ABI are being reused on GXI or GeoXO Imager. So, there’ll be two spectral bands that will be added for low-level water vapor and then, there are seven of the older bands, the previous bands that will get increased resolution,” Reith said. “So, most importantly, in the visible bands, we’re going down to 250-meter resolution, which is going to really enhance and sharpen the pictures of the weather that we’re seeing and the cloud formation and the oceans and everything else that the ABI observes.”

The first of the GeoXO satellites is targeting launch in 2032. NOAA has been working with Congress to appropriate the funds to support the endeavor. During a press briefing on Monday, Pam Sullivan, the director of the GOES-R program for NOAA, said they have been appropriated about $500 million towards a program that will cost about $20 billion over a 30-year timespan.

Calderwood told Spaceflight Now that the team at Lockheed Martin said they’re not wasting any time getting started on the first satellite.

“It’s a very aggressive timeframe and so, we do indeed need to hit the ground running. What’s key with that new GeoXO is that we’re basing it. Unlike GOES, which was off of the A2100 bus, we’re going to be using it off of the new LM 2100 and so, that has a lot of improvements in it,” Calderwood said.

She described the updates from the GOES-R series to the GeoXO as going from a car designed and built in the 80s or 90s to one designed and built today. That will include a component that allows the satellite managers wot update the software on the satellite periodically, like a phone.

“It’s providing a whole new capability of a brand new software suite and truly, it’s something that we’re working through,” Calderwood said. “We’re pulling in from key components within Lockheed and then of course, we’re also baselining it off of all the experiences that we’ve had with the GOES-R series.”