NASA is five weeks away from putting astronauts aboard a new commercial crew capsule. May 1 is the target launch date for Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft on the Crew Flight Test-1 (CFT-1) mission the International Space Station with NASA astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Sunita “Suni” Williams on board.

The capsule will launch atop a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas 5 rocket from Space Launch Complex 41 (SLC-41) at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. Liftoff on May 1 would be at 12:55 a.m. ET (1655 UTC) with docking taking place on May 2.

“This is a thrill for me and our entire Boeing Starliner program team, working with our NASA partners,” said LeRoy Cain, the deputy Starliner program manager. “I would say we are steeped in spaceflight experience in every element and aspect of human spaceflight experience.”

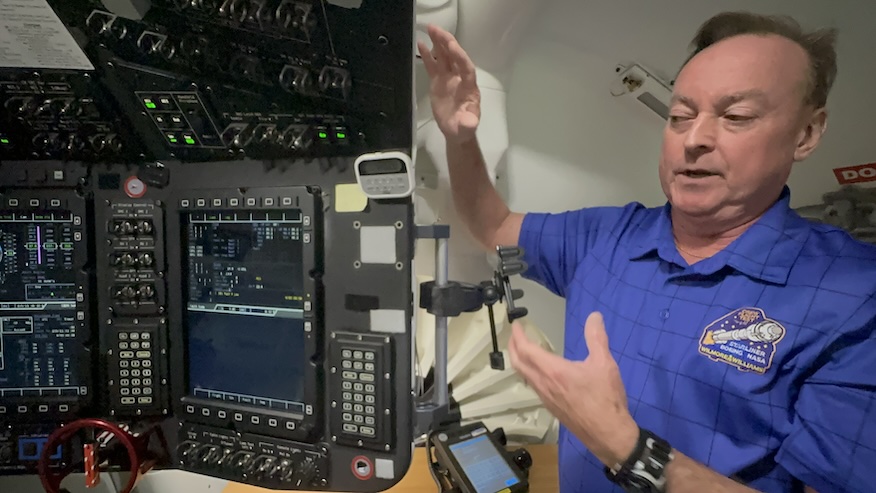

On Thursday, members of the flight control team gave members of the press an overview of the mission at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, and discussed some of the their preparations for the mission alongside the crew.

“This is the first flight of a new, crewed spacecraft. You gotta figure out how to fly it. And it started with here’s a simulator and here’s a rocket, and let’s put a crew in the cockpit and figure out how to do this,” said Mike Lammers, the CFT lead flight director who focuses on pre-launch and ascent. “We’ve been doing that for a few years. Now we’re kind of in the final phases where we train with the crew.”

Because this is a test flight, Wilmore and Williams, both astronauts with military test pilot experience, will perform some manual maneuvers during the trip to the ISS as well as on the return to Earth. Most of these actions won’t be needed during routine ferry flights to the station outside of emergency situations.

“What’s really kind of cool about Starliner is that it’s very much a pilot’s spacecraft. It’s really maneuverable,” Lammers said. “There’s close to 50 reaction-control and orbital maneuvering jets on it and there’s a stick. And what’s really cool about it is, when you have astronauts that are pilots, they really gravitate towards using it.”

Starliner will dock at the forward port of the Harmony module of the ISS. Starting with the six-month long Starliner-1 mission set for spring 2025, the spacecraft will have the capability of docking at the zenith port as well. Like SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft, Starliner-1 will also introduce the capability to relocated between ports as well.

Steve Stich, the manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, said some examples of the manual flying capabilities will be demonstrated as they approach the space station.

“They’ll go maneuver the vehicle manually to point the solar arrays at the Sun, point the star tracker, try to take star measurements to align the inertial navigation system,” Stich said. “The vehicle has great flying cues. I’ve been in the simulator and flown it myself a number of times myself and you can manually dock this vehicle, although that’s not the prime mode. The prime mode is to really fly in the automated mode with the vesta rendezvous sensor system.”

“But we’re going to test a couple of these different kinds of things during flight, take a look at the data, see how the vehicle responds,” Stich added. “Starliner flies beautifully in the simulator and I suspect it’ll do the same thing on orbit.”

Trial and error

Boeing was one of five companies selected in 2010 by NASA for Commercial Crew Development Round 1 (CCDev1) funding. Of the nearly $50 million the agency received through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), it invested $18 million in Boeing through this Space Act Agreement.

That was followed in 2011 by the CCDev2, which awarded Boeing $92.3 million and offered SpaceX its first round of funding with $75 million. Two other companies, Blue Origin and Sierra Nevada Corp., received $22 million and $80 million respectively.

Additional development awards between 2012 and 2014 brought the total funding for Boeing’s Starliner and SpaceX’s Crew Dragon to $4.82 billion and $3.144 billion respectively, according to NASA.

During Boeing’s first uncrewed orbital flight test (OFT) in 2019, a software problem caused the spacecraft to think it was further in the mission timeline than it was in reality, thereby triggering incorrect maneuvers to compensate.

As a result, OFT became a suborbital mission, which caused Boeing and NASA to take a hard look at the vehicle and figure out how to correct that and other issues that cropped up during flight. Cain said it caused them to rethink the way that they do ground testing.

“We found that we hadn’t done enough integrated tests, of the hardware-software system,” Cain said. “We did the tests that were required because those were the requirements that were written. But once again, we went back and looked and said, ‘We didn’t go far enough.’”

Cain elaborated by noting that a majority of their testing was for the expected scenarios, but not as much for contingency or unexpected events.

“We had done what we call verification and validation, VAV. We had done a lot of that early on in this program by analysis and so, we went deeper and said, ‘We want to do more real hardware-software testing,’” Cain said. “That was as a result of the lessons from OFT.”

The second flight test (OFT-2) came in May 2022 and the spacecraft was able to dock with the space station. But even then, there were some additional issues that showed up, both during flight as well as in post-flight analysis.

One of those was an imbalance in the life support system. Because there were no humans onboard to provide body heat in the capsule and create equilibrium, one of the coils in the temperature regulating system overcooled the capsule.

“In our thermal control system, was had some icing in one of the loops. And it really probably stemmed more from not having crew on board,” said Mark Nappi, vice president and program manager for Boeing’s Starliner Program. “We managed that problem and then made some changes during this last flow to make sure that doesn’t happen again. And so, what we’ll be focused on for this next flight is how the environment is controlled during the mission with crew in the vehicle.”

Chloe Mehring, who has been working on this mission since 2012, said it’s been quite a journey getting to this point: being on the cusp of finally launching people onboard the Starliner spacecraft.

“In any developmental program, things are going to take some time to make sure you get everything right. There’s always going to be ups and downs in the program,” Mehring said. “We’ve had a pretty rigorous test campaign since OFT-2 and leading up to CFT. So, getting through those and seeing the successes, I think that’s really helped out a lot with the team morale for sure.”

She said having astronauts flying onboard Starliner for the first time will give them some critical information not only about the spacecraft itself, but also some of the flight procedures.

“One thing we’re always striving to perfect or just improve on is our communication. So, this is the first time we have somebody to talk to while they’re up on the spacecraft as well,” Mehring said. “We’re really good on the ground at evaluating our systems, understanding what the vehicle is telling us, but now it’s also how do we communicate what we’re seeing with the crew members on board.”

“A lot of our training really focused on comm with the crew. Did we tell you the right thing? Did we give you enough information? And there’s a couple of things that we’re looking for some feedback from them as well,” Mehring added. “There’s very few, but there’s a couple items where we rely on the crew to tell us what they did. So, really practicing that comm a lot leading up to the mission is something that we really focused on.”

Ready to fly

Since the last briefing to the news media on Starliner in the summer of 2023, Boeing worked through some concerns with the parachute system and either removed or covered a type of tape throughout the spacecraft that had a higher probability of flammability than they and NASA were comfortable with.

They moved to an upgraded type of parachute system that was originally going to debut on the Starliner-1 mission. Boeing replaced the soft link between the main chutes and the spacecraft. They also made a change to increase the strength of one of the textile joints in the parachute.

These modifications were tested during a drop test at the U.S. Army’s Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona on Jan. 9, 2024. A C-130 cargo plane deployed a test article with the parachutes supporting its descent.

As for the tape issue, Nappi said teams “removed nearly a mile of tape from the vehicle and mitigated about 85 to 90 percent of the areas that the tape in installed on the vehicle.”

Responding to a reporter question on Friday regarding questions about safety and Boeing, NASA’s Steve Stich said the company’s handling of the parachute and tape issues were two examples of how Boeing, alongside NASA, was working diligently to ensure that the spacecraft would safely transport Wilmore and Williams.

“We had people side-by-side inspecting the tape, inspecting the wiring after the tape was removed, making sure that was done properly. Same thing wit the parachutes,” Stich said. “So the process is a little different than aviation, where I would say NASA’s more side-by-side. We’re talking two spacecraft that are going to fly on multiple missions. And so, a lot of individual care and feeding goes into every single one of those spacecraft and NASA side-by-side with Boeing.”

“Boeing designed and built the vast majority of the space station itself. They are our primary sustainer and they’re responsible for the safety of all the equipment they built, plus integrated safety across our entire spacecraft,” said Dana Weigel, NASA deputy manager of the ISS Program. “And so, the processes that we’re talking about, that we use together for human spaceflight, have been around… This is not Boeing’s first time to deal with the human spaceflight safety.”

Right now, the Starliner spacecraft is being fueled at Boeing’s facilities at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Around April 10, they plan to roll the vehicle out to the pad at SLC-41 to be mated with the Atlas 5 rocket.

Days before launch, Wilmore and Williams will participate in a crew activity day, or a dry dress rehearsal, during which they and the rest of the mission team will go through a full launch day run-through, minus fueling the rocket and launching.

The full stack will then roll out to the pad about 24 hours before launch. Cain said it has been quite the saga to reach this moment, but he said folks on both the Boeing and NASA side of the equation are feeling good about where they are in the process.

“We’re thrilled to be here at this point. We have more work to do. We’ll no doubt have other challenges as we continue to fly Starliner, but this is a big opportunity for us, a big step in the process,” Cain said.